What Changed-and Why It Matters

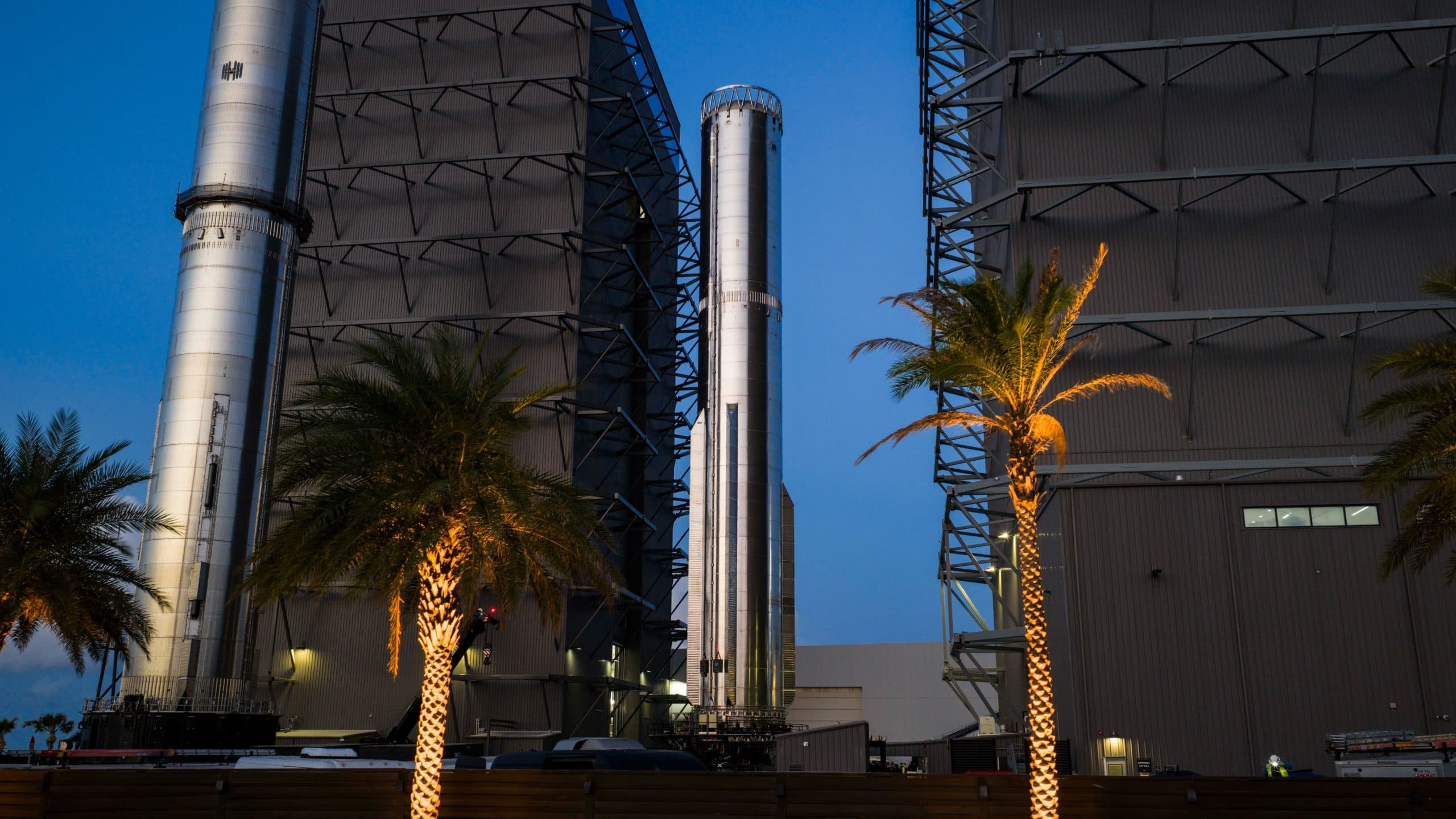

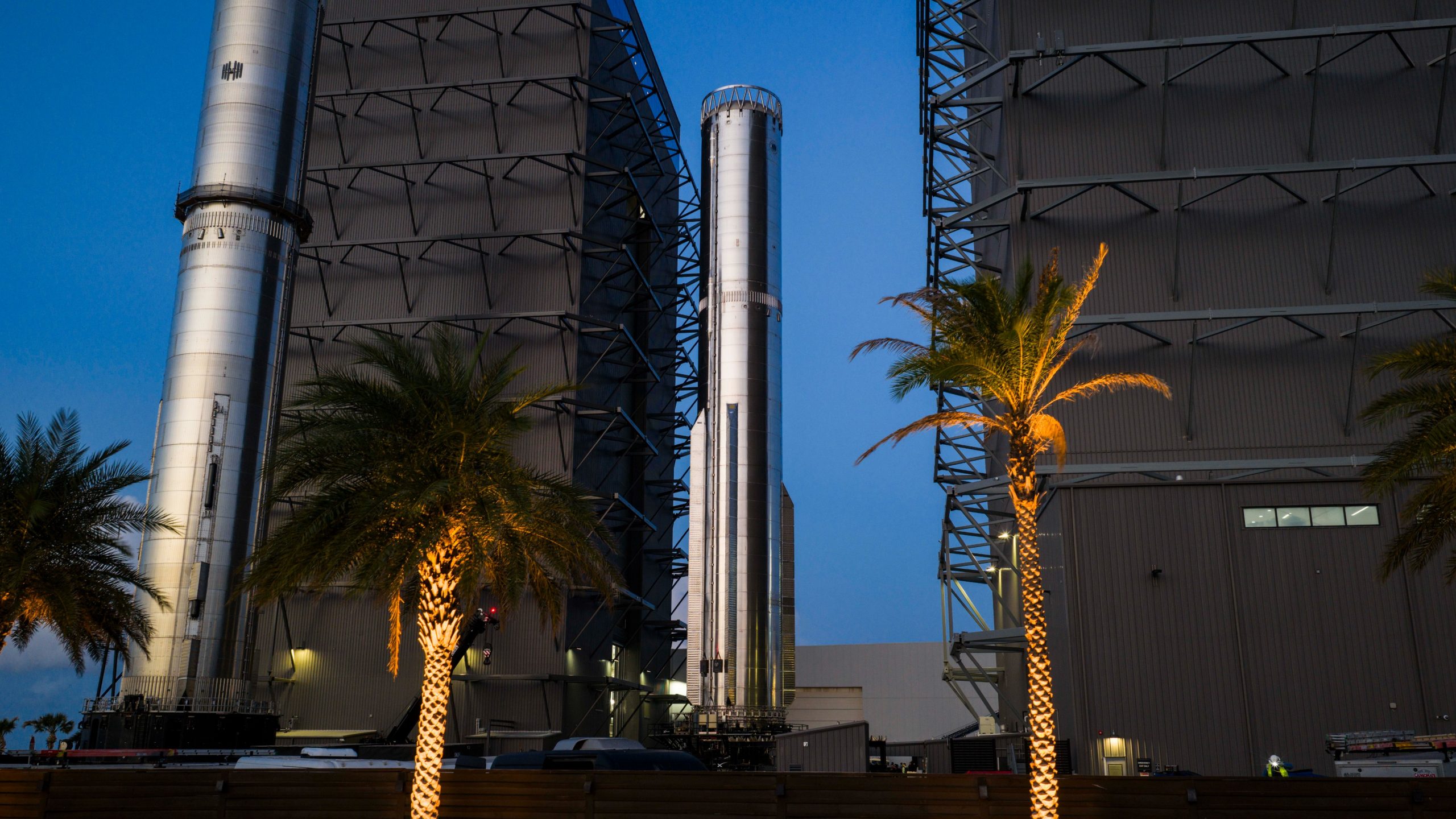

SpaceX’s newly built Starship Super Heavy booster, described as the first major element of the Starship V3 upgrade, suffered a partial structural explosion during early ground testing at Starbase, reportedly before engines were installed. The incident appears isolated to the booster and test equipment, but it introduces immediate schedule risk to SpaceX’s aggressive 2026 plan, especially the in‑orbit refueling demonstrations NASA requires before a crewed lunar landing. Any delay here raises execution risk for NASA’s Artemis timeline and narrows SpaceX’s lead over Blue Origin in lunar capability maturation.

Key Takeaways

- Short-term slip risk: Repairing a structurally damaged booster and reviewing the test stand will likely take weeks to months-not days-pending root‑cause findings.

- Preliminary cause points to pressurization hardware (e.g., a COPV) rather than engines; if confirmed, fixes could be more straightforward than propulsion redesign, but still require re‑qualification.

- V3 validation now starts under a cloud: structural and pressurization margins will face deeper scrutiny, adding test cycles before flight.

- NASA impact: in‑orbit propellant transfer demos—gating items for the Human Landing System—could slip, affecting the 2026 crewed landing target unless mitigations are adopted.

- Competitive pressure: Any Starship delay compresses SpaceX’s advantage while Blue Origin races to mature its own lander and heavy‑lift cadence.

Breaking Down the Incident

Based on early reporting, the explosion occurred during an initial pressurization phase before the ~33 Raptor engines would typically be installed on a Super Heavy. That places the likely failure vector in ground and tank pressurization systems such as composite overwrapped pressure vessels (COPVs), plumbing, or valves. COPV failures are a known aerospace risk: they can create high‑energy fragmentation even without propellant ignition. If a COPV or associated plumbing failed, SpaceX will need to inspect design, placement, shielding, fill/vent procedures, and rate‑of‑rise parameters.

The damage assessment will determine the recovery path. Limited structural damage to a single tank section could be repairable, but any deformation in critical load paths or welds often triggers scrapping a section and rolling a replacement. Test stand integrity also matters: if ground systems absorbed blast loads, SpaceX must re‑certify the stand before resuming V3 testing. Historically, Starbase has recovered from ground test anomalies within weeks to a few months, but V3 introduces new variables that will extend verification.

Why This Matters Now

NASA’s crewed lunar landing plan depends on SpaceX demonstrating high‑cadence Starship flights and in‑orbit cryogenic propellant transfer—both new to operational spaceflight. The first V3 boosters and ships are expected to underpin that demonstration series. A pressurization‑related failure prior to engine installation isn’t catastrophic for the program, but it forces rework and a deeper test envelope expansion just as SpaceX needs to accelerate cadence. Each extra test cycle adds days to weeks; design changes requiring hardware swaps can add months.

The broader risk is integration. Starship’s path to lunar readiness is not one demo; it is a chain of dependencies: booster reliability, ship re‑entry durability, on‑orbit loiter, cryogenic transfer, tanker choreography, and rapid turnaround. A stumble at the first link increases the probability of downstream friction, even if individually manageable.

Competitive and Policy Context

Blue Origin, selected for a later Artemis mission, still faces its own daunting milestones (heavy‑lift cadence and liquid hydrogen transfer among them). But every Starship slip narrows SpaceX’s experiential lead and gives NASA reason to diversify risk across providers. Expect tighter NASA oversight: hazard reports, corrective action plans, and added verification for pressurization subsystems will be prerequisites for returning to testing and, later, for flight license modifications.

Regulatory posture also matters. While this was a ground test, significant anomalies can prompt reviews that affect subsequent flight approvals. Even absent formal enforcement, insurers and range safety teams typically demand evidence of root cause, mitigations, and test stand integrity before green‑lighting the next integrated campaign.

What to Watch Next

- Root-cause disclosure: Confirmation of a COPV or valve/plumbing origin versus structural weld failure will define redesign scope and re‑qualification time.

- Hardware disposition: Whether SpaceX repairs, replaces a section, or rolls a new V3 booster will signal timeline impact.

- Test cadence: Resumption of cryogenic proof tests, followed by spin‑primes/static fires, is the near‑term indicator for schedule recovery.

- Refueling demo sequencing: Watch whether SpaceX reorders milestones—e.g., more ship‑only tests—while booster repairs proceed.

- NASA gating: Any change to the entrance criteria for propellant transfer demos or additional readiness reviews will hint at 2026 viability.

Operator’s Playbook: What to Do Now

- NASA and mission integrators: Rebaseline the critical path with explicit contingency for pressurization redesign and added verification. Treat the first successful on‑orbit propellant transfer as the real schedule anchor, not internal test dates.

- Commercial payload teams planning Starship rides: Maintain dual‑path launch options through 2026 where feasible. Lock interface requirements, but keep mass and fairing flexibility to preserve alternate launchers if needed.

- Suppliers (pressurization, valves, COPVs): Proactively tighten inspection regimes (NDI, burst testing, lot traceability) and prepare rapid design iterations. Expect elevated documentation and acceptance testing from SpaceX and NASA.

- Investors and partners: Track hard indicators—stand repairs, new V3 rollouts, return to cryo testing, static fires, and integrated flights—before adjusting 2026 revenue or milestone expectations.

Bottom line: This is a survivable setback, but at a critical moment. If the cause is confined to pressurization hardware and corrective actions are fast, V3 can still support a late‑2026 refueling demo. If not, expect meaningful spillover into 2027 plans—with corresponding shifts in NASA’s sequencing and a tighter race with Blue Origin.